What is a democratic internet, and how does it intersect with the evolving nature of HCI?

Connectivity has changed everything. In fact, experts like Elizabeth Gerber, professor and co-director of the Center for Human Computer Interaction + Design at Northwestern University, say there is not a single aspect of many humans’ lives that is not touched by near-ubiquitous internet access and adoption of connected devices. And while “near ubiquitous” is not the same as ubiquitous and there are still a great number of people without easy access to an internet connection, Gerber says for those who do, computing technology is becoming as invisible and essential as oxygen. As a result, many forget the extent to which they have set up their lives and businesses to depend on it.

The internet is a powerful tool, and humans can use it in many powerful ways—including to create social change. Institutions, corporations, and governments can also use it in powerful ways, and some may not like the result. Alan Dix, director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University, suggests it has done nothing short of change the balance of power in society. “The internet has certainly allowed all sorts of pressure groups and activists to communicate and publicize issues that would otherwise have been impossible,” he says. “Whether this is wholly good or bad depends in part on the group and how one feels about it. Certainly, it changes the balance of power in society—and maybe the real tell (is that) one of the first things non-democratic governments do when they feel under popular pressure is to restrict or shut off the internet.”

This is a reality that prompts asking some serious questions. In what ways has the internet become a tool for promoting or squelching democracy? What exactly is a democratic internet, and is the current internet even close to this ideal? Also worth exploring is the intersection of HCI (human-computer interaction) and democratic internet. And while usability is certainly the entry point for any tech and all of its downstream effects, HCI isn’t just about UX (user experience) anymore—at least it shouldn’t be. It’s about putting the human at the heart of everything. And that means every human, not just the privileged few.

A Democratic Internet

Gerber says connectivity has the potential to support or hinder democracy. “Democracy depends on representation and civic participation from ordinary citizens,” she says. “Connectivity and the internet allow ordinary citizens to participate cheaply and quickly. They can share ideas and preferences for new policies with politicians. On the other hand, connectivity and the internet can inhibit democracy through the rapid and broad spread of misinformation, decline of independent journalism, and surveillance capitalism—specifically targeting individuals based on the collection of personal data.”

Similarly, John Carroll, professor and director of the Center for Human-Computer Interaction at Penn State, says there are both positive and negative ways the internet affects democracy. “Massive, crowdsourced information exposes many things that were traditionally invisible, such as the non-withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukraine. Everyone in the world knows they lied, and it only took one day,” he says. “Disinformation and misinformation are also a sad part of the internet, and (this) undermines the possibility of any democracy anywhere.”

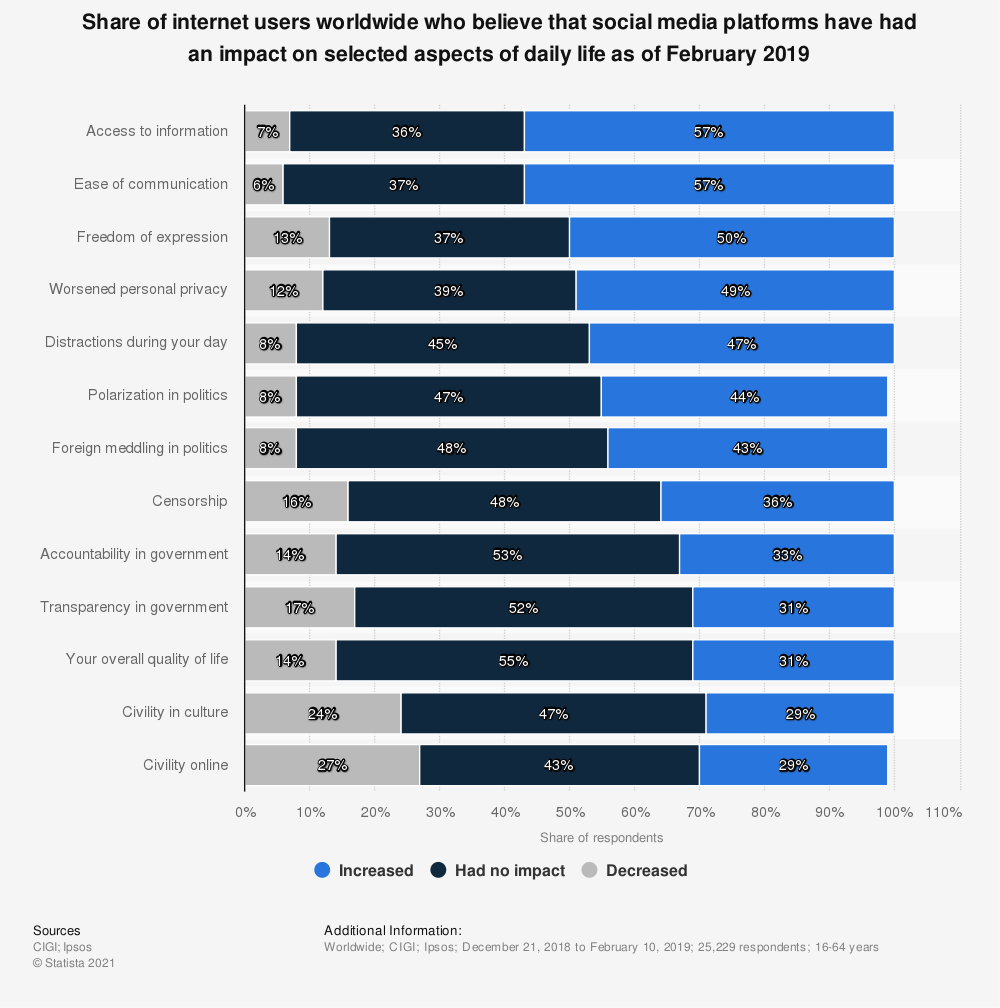

Abbas Moallem, adjunct professor at San Jose State University and UX architect and director at UX Experts, says without question, the internet promotes democracy, because communicating with others on a mass scale makes people aware of what is happening in their community and worldwide. “Even in the most authoritarian systems, people still find a way to get connected and be informed,” he explains. “However, the danger of influencing people’s opinions through what is known as ‘fake news’ is also a real danger to democracy. Social media greatly influences and shapes people’s voting and actions and their participation in a democratic election. The Cambridge Analytica case is an excellent example of how social media influences people’s opinions and votes. Many dictators try to limit people’s access to the internet and information. Others provide free access but use it to control people and influence their votes. Interesting, right?”

Mark Ackerman, professor of human-computer interaction and other disciplines at the University of Michigan’s School of Information, suggests the internet’s ability to tear people apart sometimes overshadows its ability to bring people together. “We all thought that the internet would bring more information to people and draw cultures together. We were wrong,” he says. “The internet can bring more information to people, make them better citizens, and allow people to exchange ideas. It can also sow dissention, give people misinformation, allow people to engage in vitriolic debates, and create what appear to be information bubbles.”

To take a more 10,000-foot view, beyond the internet’s ability to foster (or suppress) democracy and/or democratic ideals, there is also the broader concept of a democratic internet—one Ackerman defines as an internet that runs according to democratic principles. Ramesh Srinivasan, professor at UCLA who explores technology’s relationship to political, economic, and cultural life, defines a democratic internet as one where digital technologies support not only the interests of people, including the ability to share and communicate, but also the interests of a more economically and socially just society and world.

“A democratic internet would be one where we all would gain from the use of these technologies,” Srinivasan says, admitting that this is pretty much the opposite of what has happened. “The wealthiest companies in the history of the world are not only manipulating what we see through their targeted algorithms (and) what they call personalization algorithms, but they also are making astronomical amounts of money in a world that seems to be more unequal economically by the moment.”

For Srinivasan, a democratic internet would be one with checks and balances. Naturally, businesses would be part of the equation, but they would be regulated so everyone could gain. “Imagine if the entire public had 1% or 5% equity, a public-owned part of these companies,” he says. “That would mean the incredible value these companies have would be also shared with the rest of us thanks to our initial investment in the internet. That would be a far more democratic outcome.”

A democratic internet would also ensure various communities are not marginalized or discriminated against. “We’re seeing many examples of how various sorts of technological platforms are turning out to have discriminatory biases with women, with people from working classes, with people of color,” Srinivasan explains. “A democratic internet would be a place where different communities and individuals would be protected and uplifted by that internet.”

So how do we get there? Could a broadened approach to HCI and HCD (human-centered design) be the key to creating a more democratic internet?

5 Characteristics of a Democratic Internet

- A democratic internet supports an economically and socially just world.

- A democratic internet has checks and balances.

- A democratic internet does not exclude but uplifts all communities and individuals.

- A democratic internet is transparent and accessible to everyone without interference or filtering by providers.

- A democratic internet respects users’ privacy.

The Evolution of HCI

Penn State’s Carroll says a democratic internet promotes thinking, imagination, questioning, and learning. It challenges bias, hatred, privilege, laziness, and the acceptance of tyranny. “This is directly connected to HCI,” he adds. “If people are not enthusiastically engaged by technology, then it really does not matter if that technology could liberate them or not. The potential for liberation that can never be realized because the technological infrastructures don’t work for humans is meaningless. People make technologies ‘work.’ Usability is the entry point for any technology-mediated advancement.”

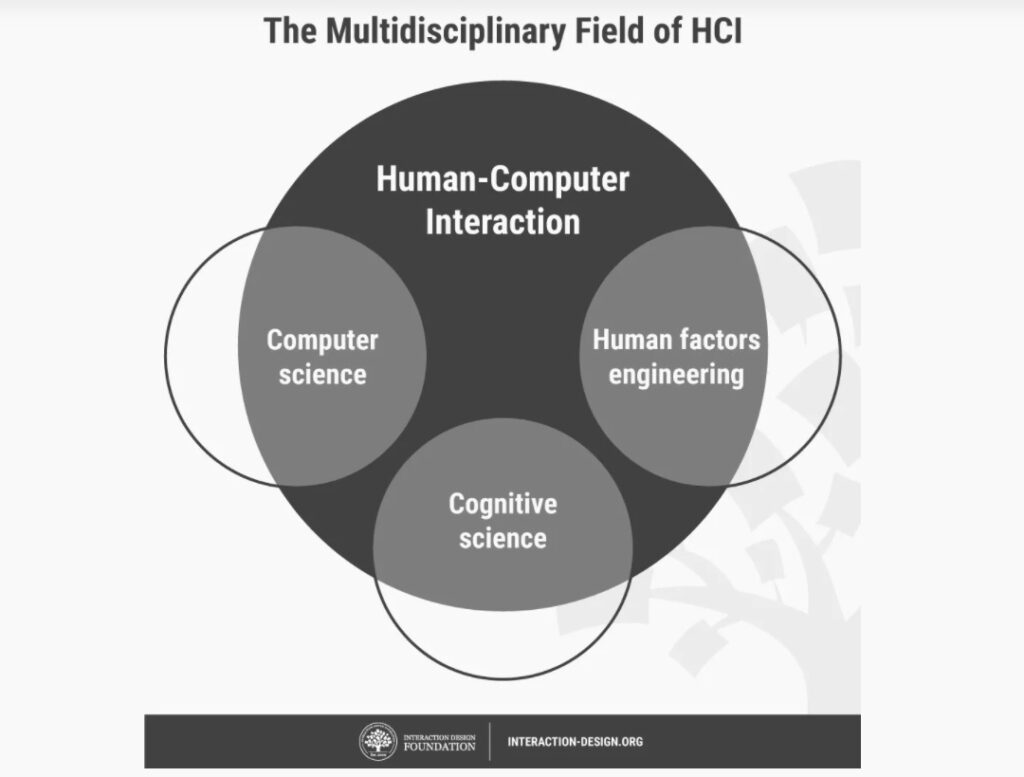

The University of Michigan’s Ackerman points out there is both a narrow and a broad definition of HCI that’s useful to consider here. “HCI, in the narrow sense, is about usability and usefulness. I hope that a big part of it can be used in designing and constructing future virtual worlds, dealing with sustainability, and tying people together in productive ways,” he says. “Most commercial developers would acknowledge the importance of considering the user, and that’s an enormous improvement from when I started my career back in the 1980s.”

HCI in the larger sense, though, considers the socio-technical and how the two are necessarily interwoven. “Computational systems necessarily exist in a social context,” Ackerman explains. “Their designs spring out of cultural and societal assumptions, and they further reinforce some cultural and societal beliefs and structures and leave other potential beliefs and structures behind. Thinking about the multiple layers is critical to understanding how to better design apps and systems, so that we at least try to consider the potential liabilities, issues, and vulnerabilities, instead of merely celebrate technological utopianism. I love technology; it’s why I do what I do. But we shouldn’t be building blindly anymore.”

UCLA’s Srinivasan similarly points out HCI has traditionally focused on ensuring computers and computer systems are communicative, legible, and interact in a smooth and efficient way with users. “I rarely hear in HCI work, even now, of thinking about computers serving human needs. (And) when I say human needs, I mean not us being able to use it—like a usability thing—but really who we are and what we believe in and what we want. So, therefore, I think real human-computer interaction work needs to deal with this question of what is a democratic internet and how do we get there?”

To get there, experts like Srinivasan suggest public audit and governance of private technology companies that are monetizing consumers’ public lives. He says: “We need both economic and governance proposals that ensure that the public is uplifted with these technological changes, and that is really not what’s happening.” Perhaps the first step is coming together to address the question: What does a democratic internet look like? Srinivasan says in the U.S., there is bipartisan consensus that the status quo is not working. If parties could come together to outline what a democratic internet should look like, then perhaps the government could move forward to regulate it accordingly.

“We need to completely expand our thinking about HCI outside the limited legibility of an interface, which has been mostly what it’s about,” Srinivasan concludes. “I would like for us to think more broadly about the technological-human relationship—to think about what a democratic vision of that would look like.”

Perhaps the term “HCI” is part of the problem. Penn State’s Carroll sees HCI as a slightly outdated term for HCD. “HCI tends to include many professionals who are not concerned with transforming society through socio-technical design of real and critical digital artifacts, whereas HCD emphasizes that the heart of the enterprise is designing the future.”

Northwestern’s Gerber says through the lens of designing technology-based solutions and systems, human-computer interaction and human-centered design are similar in that both are concerned with design of technology solutions and systems from the perspective of people. “Both maintain the perspective of people throughout the design process from understanding the problem and generating ideas to developing and implementing solutions,” she says. “Historically, HCI has been more concerned with usability, efficacy, and efficiency, whereas human-centered design is concerned with usability, efficacy, efficiency, as well as enhancing mental, physical, and spiritual wellbeing, but this distinction is fading.”

No matter what we call it, Swansea University’s Dix says the human-centered part of both HCI and HCD is key. “In order to study HCI, we need to understand both humans and computers,” he explains. “Human-centered reminds us to look first at the person or people—where they are, their needs, aspirations, jobs, and lives—and only then to ask ‘how can computers help?’”

And part of that reflection should be considering how technology can support people’s core values. “Computing technology, whether it be the internet, smartphones, artificial intelligence, and more is part of our everyday lives and is here to stay,” says Northwestern’s Gerber. “We must design and use it to help us thrive as people, which means being clear about what we value.”

In many cases, people value democracy. They also value privacy. San Jose State University’s Moallem wisely points out that two fundamental principles for a democratic internet must be privacy and trust. “The people’s trust in using internet-based communication, automation, robotics, and so on is fundamental,” he explains. “For example, people will never use autopilot in cars or automated driving vehicles if they don’t trust their security. On the other hand, people’s privacy, even though that might be a little abstract, plays an essential role in the usage and trust of a system.”

Finally, it’s helpful to realize that the pieces of this puzzle are moving and evolving, in many cases at the speed of technological innovation. “We need to be humble and realize that everything can’t be foreseen, (and) one take away from HCI is that you should think iteratively,” concludes University of Michigan’s Ackerman. “We’re not going to get it right the first time. We can get better over time, however. The solution may be to consider socio-technical solutions to these problems. How might a democratic society be able to use regulation to correct flaws without straight-jacketing innovation—that’s an important question as we move forward.”

Links for Further Learning:

- “Americans need a ‘digital bill of rights’. Here’s why” by Ramesh Srinivasan

- What is HCI?

- Pew Research Center’s “Concerns about democracy in the digital age”

Want to tweet about this article? Use hashtags #IoT #sustainability #AI #5G #cloud #edge #digitaltransformation #machinelearning #infrastructure #InternetfortheFuture #privacy #legislation #connecteddevices #security#democraticinternet #connectivity #HCI #HCD