The key is to ensure health tech is affordable, accessible, and inclusive.

In the past couple of years, society has had to intensely re-evaluate how it can and should approach various aspects of public health. The COVID-19 pandemic upheaved many processes in life and business, and it vastly disrupted economies. But the silver lining amidst the horror of the disease that caused millions of deaths globally is that the COVID pandemic also broke down barriers for health tech that may save and improve millions more lives going forward.

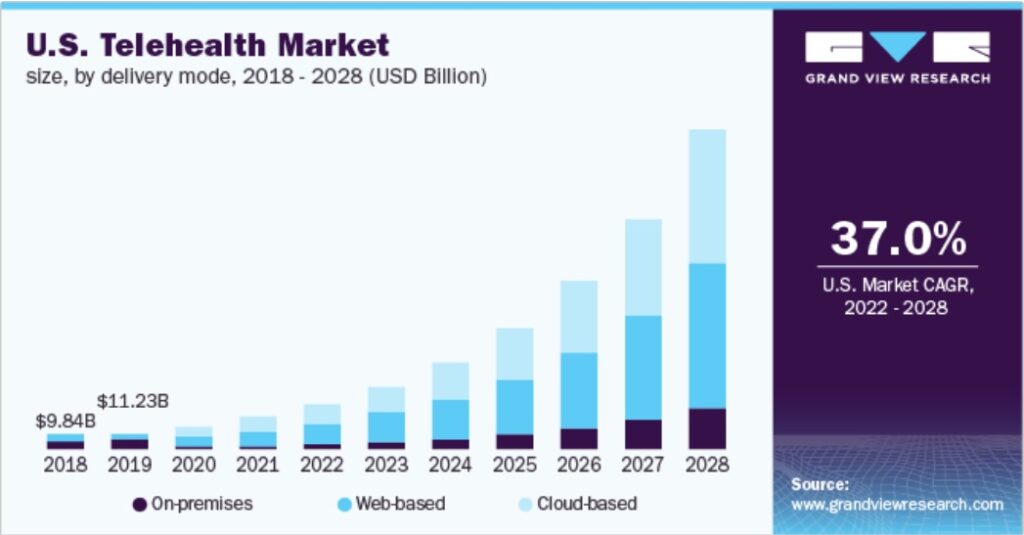

According to Market Research Future, the IoT (Internet of Things) in healthcare market is projected to reach $320 billion by 2027. Many, including Connected World, have conjectured that one of the main takeaways from the pandemic will be a massive shift to telehealth solutions. But will the shift be as massive or as straightforward as was once assumed it would be? Some experts cite concern over the almost knee-jerk reaction to “go back to normal” in how healthcare is delivered, erasing some of the progress made in health tech adoption and innovation during the worst of the pandemic.

Other large questions remain for the future of healthcare technology, including those around affordability, accessibility, and inclusivity. The future of tech-driven healthcare is exciting, and the past few years have accelerated progress toward that future in many ways, but it’s not set in stone. Will healthcare technology exacerbate health disparities? How can society find that right balance between ensuring privacy/security and being able to leverage health data for the good of public health?

Telehealth and Other Pandemic-Driven Health Trends

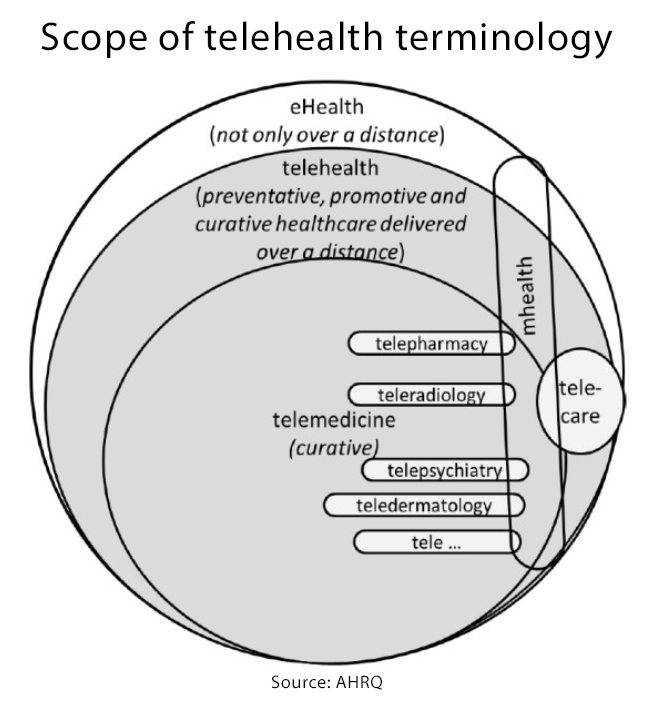

Yaa Kumah-Crystal, MD, HealthIT clinical director for telehealth and assistant professor of clinical biomedical informatics and pediatric endocrinology at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, says the biggest pandemic-driven trends have been telehealth and the growth of remote patient-monitoring options. “With the pandemic, when there were orders to be safer at home, etc., we had to quickly come up with ways that we could still address patient care needs without requiring them to come to the hospital and to the clinics to be seen,” she explains. “Certainly, there were patients that were ill enough that required hospitalizations, but to prevent the more well patients from inappropriately being exposed to things like COVID, we had to enable infrastructure to be able to see patients where they were, and this was quite a remarkable change in the dynamics of how we were delivering care.”

Kumah-Crystal says the sudden widespread use of teleconferencing platforms to bring patients and providers together made it possible to, in a way, go back to the past, when healthcare was delivered in a much more personal way. “We set up platforms like Zoom and Teams and other telehealth tools to essentially start doing house calls again,” she says. “In the past, physicians would go visit patients in their homes, check on them, (and) see how they are doing. Things changed mid-century when we kind of established these office towers where patients would come to see us. But I think things pivoted once again with the pandemic when we were able to meet patients where they were and more or less step into their homes again.”

Telehealth offers a tradeoff of benefits. Certainly, it can be a time saver, since patients leveraging telehealth don’t need to take a full or partial day off to drive, park, wait, and wait some more only to see a provider face to face for 20 minutes or less. However, not all conditions are well suited for telehealth, and both doctors and patients can benefit from being in the same room in some cases. In many circumstances, though, a telehealth visit suffices and brings a lot of value to both patient and provider.

Gil Bashe, chair global health and purpose at FINN Partners, suggests telehealth has made a profound and lasting impact but isn’t necessarily going to continue at pandemic rates. “The rollercoaster telehealth and health tech trend is both encouraging and worrisome,” Bashe says. “At the outset of the COVID pandemic, there was a 70% rise in patient virtual-care platform access; however, historically medical is driven by reimbursement patterns. Bottomline, patient use remains higher than before COVID, but continues to dip. Once high-flying telehealth stocks are taking a beating. Digital health investments have dropped this quarter. Overall, it’s still a net positive. Telehealth is now established and virtual access is a permanent part of an integrated health platform. Health tech innovation and cybersecurity continue to improve, and investment is still bountiful. Look at the long-term cultural shift—health technology and access are now a given part of the health structure.”

John Nosta, president of NostaLab, challenges the idea that telehealth is really that innovative and encourages the industry to think bigger. “While most observers of (telemedicine) will state that it’s reached an inflection point, I would argue that it’s much more a tipping point,” he says. “Some data have indicated that telemedicine trends have retreated significantly back to pre-COVID levels. So, for me, I see an elasticity to this trend that has brought us back to almost baseline. Telemedicine has also emerged as a rather anemic version that is not more innovative than a call with your doctor 50 years ago.”

Nosta says Steve Jobs once observed the early days of television were nothing more than a radio show with a TV camera in the background. “I think that’s exactly what we have with telemedicine,” he adds. “It’s just an office visit that is pushed through a Zoom call.” Looking forward, then, Nosta says the challenge goes beyond merely repurposing the age-old physical exam to reinventing the exchange of information within new “techno-human constructs.”

Shikha Anand, MD, chief medical officer at Withings, says another key pandemic-driven trend in the health space is that people have taken a greater interest in and ownership of their health. “This translates to more at-home devices, greater ownership of personal health data, and more frequent health measurements as people traveled less and were home more,” Anand says, adding that COVID broke down many barriers to health tech adoption. “On the consumer side, people were forced to rely on at-home monitoring early in the pandemic, when clinical systems were struggling to keep up with the demands of the pandemic. This increased adoption of, and reliance on, health tech. Care teams, in turn, had to adapt to stay-at-home recommendations with telemedicine, normalizing hybrid care. We even saw regulatory changes with regards to telemedicine, allowing for practice across state lines in situations where this was not previously allowed, let alone reimbursed.”

While barriers have certainly broken down over the course of the pandemic, hurdles persist. “It remains to be seen how much the evolution of telemedicine practice and regulations through the pandemic will persist thereafter,” adds Anand. “While many clinicians have become more comfortable with telemedicine, they did so in a moment where access was of the utmost importance. As access resumes pre-pandemic norms, it remains to be seen whether clinicians and clinical systems will continue to embrace telemedicine and remote monitoring to the same degree as they did during the pandemic.”

Marianna Obrist, professor of multisensory interfaces at the UCL Interaction Centre, agrees the pandemic has accelerated the use and development of digital services/technologies for remote care and monitoring and that is mostly a good thing—but she sees potential issues with these digital services and technologies creating or exacerbating healthcare disparities. “I do agree that COVID-19 has transformed and particularly accelerated the use of technology in the health and care domain,” she explains. “What was deemed a longer transition was suddenly possible in a few months. However, there is always a flip side, which in this case is based in the digital divide: lack of access to technology but also literacy to use technology, which then causes health inequality, leaving many excluded.”

As society moves toward the endemic phase of the pandemic, how can the health and tech industries leverage technology to address public health concerns, while also keeping in mind issues relating to affordability, accessibility, and inclusivity?

Paving the Way for Affordable, Accessible, Inclusive Public Health

Kai Zheng, professor in the UCI’s (University of California, Irvine’s) Dept. of Informatics and Dept. of Emergency Medicine, chief research information officer for UC Irvine Health Affairs, and director of the Center for Biomedical Informatics, Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, points out smartphones provide a valuable means to affordably reach, educate, and treat populations at scale, as can home-based care via home test kits, wearable devices, and remote monitoring devices. “(The) digital divide used to be a big concern held by many, but I think the barrier due to the cost of technology, and even technology competence, has become less prominent in the recent few years.”

Withings’ Anand agrees costs are coming down and that’s opening doors. “As consumer health devices have decreased in cost and technology has improved, it is now possible to provide consistent high-quality at-home monitoring at a much lower cost than in-clinic care. This technology allows improved access and choice of care team for many people,” she explains. “Broader availability and awareness have led to an increase in uptake of at-home measurement by consumers. This allows health monitoring to be a part of people’s routines. By measuring consistently, with the right guidance, consumers can start to see how their daily choices affect their health. When combined with behavioral nudges, they can begin to build healthier habits that will be the key to better outcomes in the long run.”

Costs are coming down, yes—but Jessie Tenenbaum, chief data officer for the NCDHHS (North Carolina Dept. of Health and Human Services), points out that smartphones and broadband internet access are not ubiquitous. “There is a major divide for those who do and do not have broadband internet access at home, and many people, particularly older people, are not smartphone-savvy,” she says. “That said, technology does provide an opportunity for both pushing information to individuals (e.g., via SMS) and pulling information from central resources (e.g., accessing health records). It can also allow for efficient collection of user-generated data, through surveys, passive tracking, etc.”

Beyond affordability, the ethical challenge of making sure technologies are inclusive and accessible to all abilities is of the utmost importance. Obrist from the UCL Interaction Centre admits it’s a difficult challenge the industry is working to address. “There are many efforts in the field of HCI (human-computer interaction) to design more inclusive and accessible interfaces/devices and digital technologies,” she explains. “The community has established a framework of guidelines and inclusive design principles that are increasingly applied in practice yet are often an afterthought in many technology companies. Despite good intentions, technology companies often have other priorities first (e.g., getting their technology to work, secure funding for the continuous development) before tackling accessibility issues. Close engagement with relevant stakeholders and particular end users is key to ensure inclusiveness and a continuous responsible reflection about technology innovation.”

Vanderbilt’s Kumah-Crystal adds the first step toward making sure health tech solutions are inclusive and accessible is to make sure these questions are asked upfront and not as an afterthought. “Often when we are developing new technologies, we’re always very optimistic and blue skies thinking about all the wonderful things they can solve,” she says. “And then it’s usually after the fact that we identify that machine learning models didn’t have a large-enough data set to take into consideration people of different races and ethnicities (and) therefore, face identification will incorrectly identify people of African-American descent, and things like that … but I think asking these questions upfront and having that be part of the driving factor to say, how can we establish a workflow for telehealth that is inclusive? I think is just the most important part.”

5 Barriers to Health Tech Adoption

The COVID-19 pandemic knocked down barriers for digital health, but will that momentum hold steady in the coming years, or will it wane as society approaches the endemic phase of the pandemic? Here are five of the top remaining barriers to health tech adoption:

- Fear of change and the unknown

- Privacy/security

- Cost/affordability

- Inclusivity and accessibility concerns

- Complexity

Affordability, accessibility, and inclusivity are just three of the barriers still facing the health tech space. In fact, Obrist says technology is only one piece in the puzzle of addressing public health concerns; another crucial part is people. UCI’s Zheng says the public’s health literacy is a big barrier to effectively using technological solutions, consuming health information, and adopting behavior change. “Access to care and technology is not the main issue, but the lack of patient initiative, lack of information, and lack of health literacy continue to be factors limiting effective use of the resources readily available,” he explains. “Horrible user interface and user experience designs of technologies continue to discourage dissemination and add undue burden to users.”

Consumer education is necessary to address health literacy concerns. João Bocas, CEO of Digital Salutem, says: “There (is) a huge piece of work to be done in order to maximize technology’s impact, and that is health education and teaching people about their health—basically making healthcare uncomplicated and remove perceived barriers to human health. Sometimes, I truly believe that there is a strong focus on technological side and we forget that health is about people, business is about people, technology is about people, and life overall is about people.”

“The people” are also concerned about privacy and security. Kumah-Crystal says a person’s reluctance to adopt health tech tools sometimes goes much deeper than cost. “There’s just different considerations around different cultures around the trust of the devices and the technologies and the new workflows,” she says. “(When) interviewing patients about reluctance to use telehealth and telecare, people had concerns about data privacy and about how the information was being managed and being able to maybe speak freely about some of their concerns over a device that could potentially capture recordings and stuff like that. It wasn’t always about ‘I can’t afford this tool,’ but ‘I want to make sure that people are managing the information that I have to share in an appropriate way,’ and that was an interesting thing to learn.”

NCDHHS’s Tenenbaum says one question the industry should be asking is how can it balance the desire for/right to privacy with the potential advantages of leveraging big data for the collective good? “(The answer is) through clear communication (about) what is being collected and why, the opportunity for people to opt out if desired, establishing trusted relationships, (and) increased science communication to the public,” she says.

During the heat of the pandemic, there was a race to make care happen, and concerns like privacy and security took a back seat. Digital Salutem’s Bocas says as a result, there has been a big shift in the way healthcare is delivered, and it has also become clear that the industry was moving too slowly pre-pandemic. “Now that we realize what we were not doing and we were acting too slow, how can we change that?” he asks. “Innovation is about action, and action is about doing things quicker and well. The industry needs to move accordingly.”

And while no one would wish to relive the past two years again, the wisest move now is to leverage lessons learned to benefit public health and to make healthcare better. Kumah-Crystal says it’s going to be interesting to see how things shake out in the next few years in terms of technology, ensuring it’s equitable and accessible, and recognizing it’s not always financial barriers but also trust dynamics and other things that play into why people choose or do not choose to use health tech tools available to them.

All in all, she feels fortunate to have been part of this important moment in healthcare. “I imagine being an old lady and talking to my great, great grandkids about 2020 and how that really changed the way we deliver care. It’s been fascinating,” she says. “And I think we’re just so fortunate to have had the technology we had to support us through these trying times. Imagine if this happened in the 90s when all we had was AOL and dial-up. Can you even imagine? How would we have fared, then? I think we live in a remarkable time with remarkable people doing remarkable things. I’m really excited to see what comes next.”

Links for Further Learning:

- IoT in Healthcare Market

- Evidence Base for Telehealth

- Clinical Utilization of Digital Health Technology

Want to tweet about this article? Use hashtags #IoT #sustainability #AI #5G #cloud #edge #digitaltransformation #machinelearning #infrastructure #bigdata #cybersecurity #healthcare #digitalhealth #publichealth #COVID19#telehealth #telemedicine #privacy #Withings #DigitalSalutem #NostaLab #FINNPartners