If net-zero emissions is likely on a global scale, it’s going to require ‘electrifying everything’.

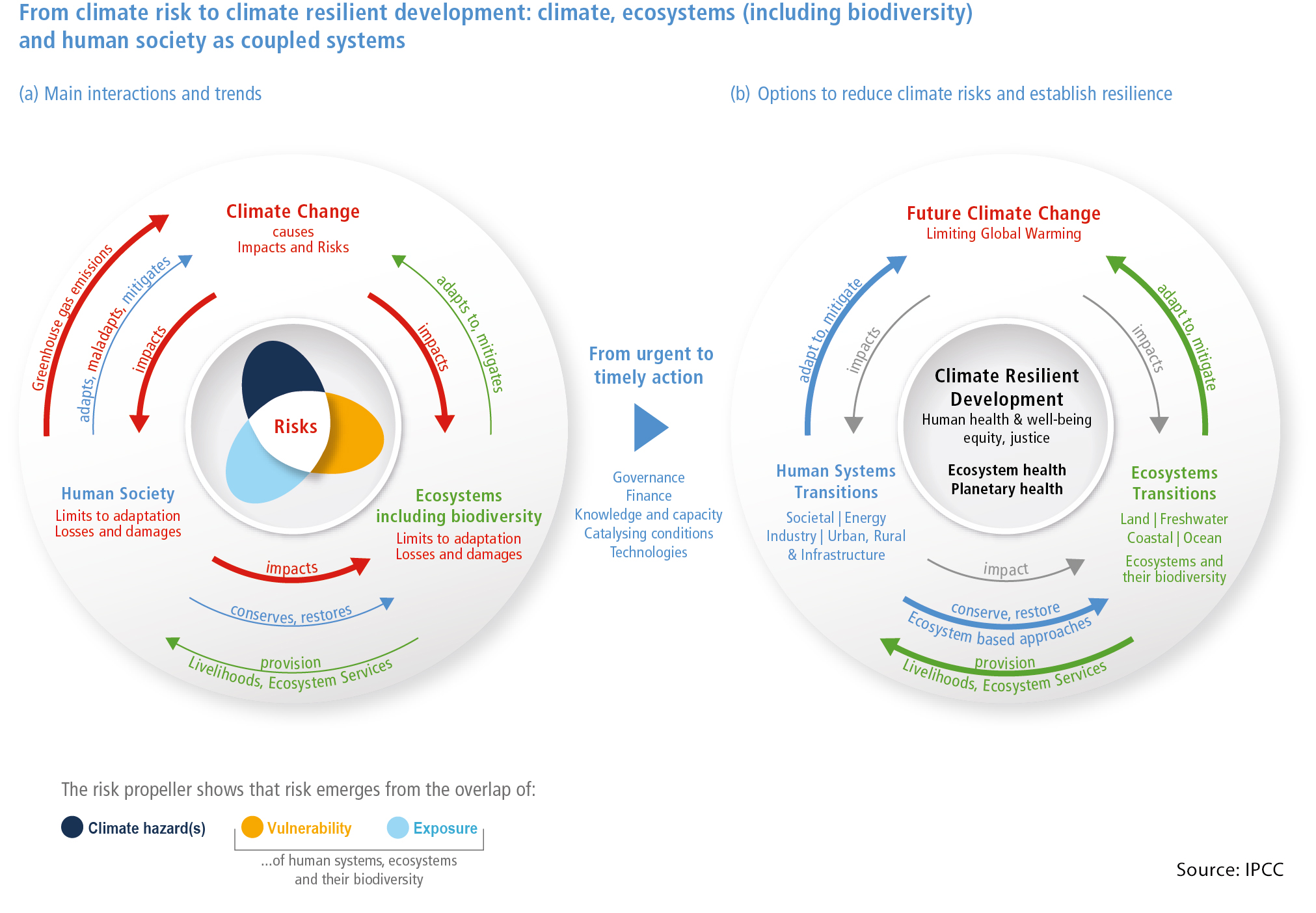

The reality and gravity of the climate crisis is continually setting in, especially as extreme weather events continue to negatively impact economies and as governments, business leaders, and ordinary citizens—not just scientists—are crunching the numbers. How can each nation do its part to keep global warming from reaching the determined tipping point—2 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels? The Paris Agreement has spurred many commitments that will go a long way in reducing GHG (greenhouse gas emissions) as soon as possible, with the hopes of ultimately reaching a “climate neutral world by mid-century.”

The U.S.’s most recent commitment came from President Biden in April 2021, with the new target being a 50-52% reduction in net GHG pollution from 2005 levels in 2030. Policy will undoubtedly play an important role in helping the U.S. meet this target, and technology will play another important role. Some experts say for the most part, the technology to do what the world needs to do to reach net-zero already exists, it’s just a matter of creating the behavior change necessary to meet this lofty goal. What steps must the U.S. take for it to hit the 2030 target? What steps must every nation take to reach zero global emissions—and is this even possible?

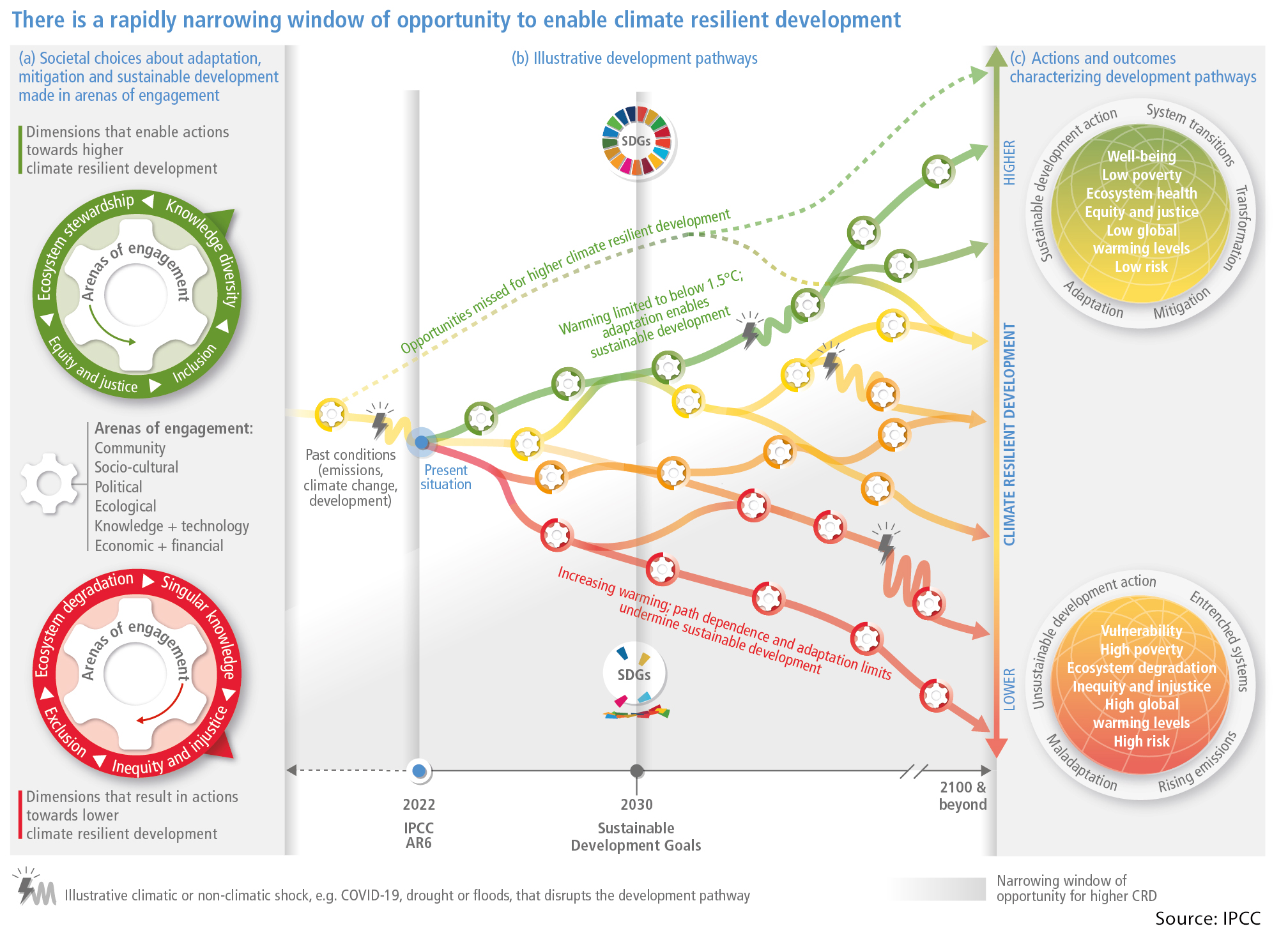

The March to 2030

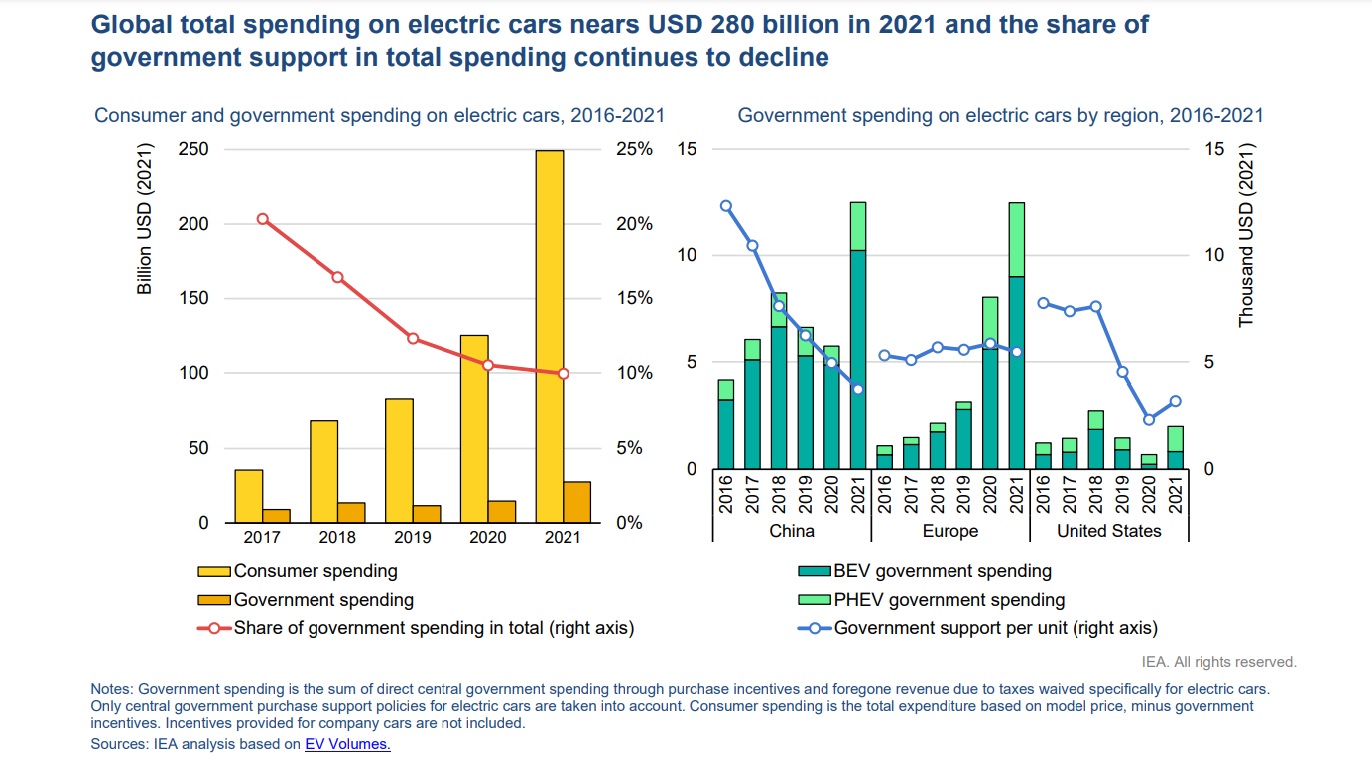

Several trends—in mindset, technology, policy, energy, transportation, and beyond—are converging as the U.S. and other global nations march toward net zero and/or other carbon-reduction goals. Edward Sanchez, senior analyst of automotive for Strategy Analytics, says two important trends include the near-universal agreement that something needs to be done and the decreasing cost of technologies that can help. “The scientific consensus about climate change is becoming increasingly unanimous,” he explains. “The cost of ‘green’ technologies in most—but not all—cases is declining, making more efficient technologies more practical now than they were in decades past. As an example, the cost of solar is nearly one-third what it was just 10 years ago.”

Sanchez points out that recent events have set back some progress on costs. “A recent countervailing trend is the spike in commodity prices for some elements used in the making of EV batteries, such as nickel, cobalt, and lithium,” he says. “Obviously, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and Russia also weaponizing its natural resources by cutting off its natural gas supplies to nations that they feel are taking an antagonistic and negative stand against some of its national interests has added greater urgency to energy diversification.”

Thomas Longden, a Fellow with the ANU (Australian Natl. University) Energy Change Institute’s Grand Challenge–Zero-Carbon Energy for the Asia-Pacific, says in terms of technology trends, the cost of solar panels has changed the game for electricity generation. “We are seeing the implications (of lower solar costs) with a higher rate of installations of roof-top solar, and cost declines are predicted to continue,” Longden explains. “They may stall in the next year or so but are expected to decrease. And the costs of EVs (electric vehicles) are also expected to fall with more vehicle options getting released.” He also agrees the mere declaration of net-zero targets is an important trend that’s helping to concentrate the focus on achieving emissions reductions across all sectors.

Alan Jenn, assistant professional researcher at the Plug-in Hybrid and Electric Vehicle Group of the ITS (Institute of Transportation Studies) at UC Davis (University of California, Davis), says many trends toward decarbonization across the world begin in policy. “Many countries and regions first began with general carbon emissions targets, whether that be from the Paris Agreements or from individual emissions targets, such as California’s AB32,” he says. “In the last few years, a substantial number of more specific goals and regulations have been passed to help meet the original emissions targets—e.g., California’s Advanced Clean Trucks, Zero Emission Vehicles regulation, Biden’s Clean Energy order, EU’s CO2 emissions standard, China’s NEVs (new-energy vehicles), etc.”

In transportation, this upswing in regulations and guiding policy has led to a rapid transformation of the vehicle sector towards electrification. “In just the last two years, the sales of EVs in the light-duty sector has doubled and tripled in many countries,” Jenn says. “Following in these footsteps are technology transitions in the medium and heavy-duty sectors towards electrification.”

And yet, despite these promising trends and others, Jenn says it will still be very difficult to meet many of the carbon targets necessary to keep global warming and climate change in check. “A 50% reduction in GHG emissions in 2030 relative to 2005 will require tremendous cuts in emissions across all sectors. It will not be possible to reach this goal in just one sector,” he adds. “This means a large shift towards clean energy sources in the electricity sector (including) large deployment of wind and solar, since the expansion of nuclear is not really being pursued in the U.S., continued and accelerated adoption of electrification in the transport sector, … (and) in commercial and residential sectors, buildings must improve efficiency. Again, these goals will be difficult to achieve, but setting targets will enable and motivate regulatory agencies to begin setting specific regulations to help meet them.”

Jeff Allen, executive director of Forth Mobility, says the answer is relatively simple to the question of how the U.S. can meet its 2030 target. “We need to move quickly to electrify everything that moves—starting with cars, transit buses, school buses, and trucks,” he says. “The investments in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law will help a lot, but we’ll need complementary investments from electric utilities, car companies, states, and cities to expand access to electric vehicles and charging. We also need to keep working to help people more easily choose options other than cars with one person in them—options like walking, biking, and transit. Electric bikes and scooters can help here by making it easier for more people to use these alternatives as practical everyday transportation.”

5 Steps toward ‘Electrifying Everything’

Jeff Allen, executive director of Forth Mobility, says a key step toward meeting the U.S.’s climate goals is to “electrify everything.” To move in that direction, the U.S. needs to:

- Make sure people have good information about EVs and mobility options.

- Jumpstart a convenient and affordable network of charging stations.

- Produce more models and styles of EVs—from electric bikes to pickup trucks and SUVs—to appeal to all drivers.

- Build out a robust, sustainable, and more just supply chain for EV and battery manufacturing.

- Continue to convert electricity generation to clean renewable sources.

“Electrifying everything” may be a simple-ish answer to the question of how the U.S. gets to its 2030 goal, but the implementation of this is not simple (or simple-ish) at all. Zoe Long, research manager for START (Sustainable Transportation Action Research Team) at Simon Fraser University, points out there are many subsectors within the transportation sector, including passenger transportation (how people get around) and freight transportation (how goods get around). “Each has its own potential advantages and barriers with electrification,” she explains.

“Many nations have set goals to phase out sale of new fossil fuel-powered vehicles—for example, in Canada by 2035—in favor of zero-emissions vehicles, which typically means electric vehicles. My opinion is that the technology will be ‘ready’ by then, but other challenges remain, such as infrastructure provision—at home and outside of homes—and supply bottlenecks. Electricity grids will also have to keep pace with demand increases, and electricity generation will need to be increasingly low carbon to meet broader GHG reduction goals.”

UC Davis’s Jenn predicts EV sales will reach 90% or more of the market share of new vehicles sold sometime in the 2030-40 timeframe. “Hopefully this would translate to 90% or more of vehicles cumulatively on the road in the 2040-‘50 timeframe,” he adds. Freight transportation, which includes heavy-duty trucks, trains, ships, and aviation, is a bit of a different story. SFU’s Long says there are other challenges to electrifying freight, such as battery capacity and suitability. Therefore, it will likely take longer for this section of the sector to electrify. For instance, Strategy Analytics’ Sanchez predicts it will likely be 2040 or later until the heavy truck sector is predominantly electric.

Forth Mobility’s Allen says because the cost and performance of EVs and components, including batteries, have continued to improve dramatically, society is now just about at the point where a new electric car is the same price as a comparable gas car and the electricity to fuel it costs the equivalent of about $1 a gallon. “With gas prices high and volatile, there’s more interest than ever in ways to transition to lower and more predictable technology,” Allen adds. “It will take a long time for the fleet to turn over to the point where every single car is electric, but I expect by the 2040s gas cars will start to look like flip phones.”

Is Net-Zero Emissions A Pipe Dream?

Assuming many nations meet their goals set forth in Paris, is the climate crisis averted? Not necessarily. The goal is not just to keep the planet inches away from the tipping point but to reach net-zero emissions on a global or near-global scale. But is this even possible? If so, is it probable?

John Paul Helveston, assistant professor at The George Washington University who studies technological change with a focus on accelerating the transition to environmentally sustainable and energy-saving technologies, says reaching net zero globally will require the same broad strategies the U.S. will need to employ to reach its 2030 carbon-reduction goals. “Reaching net zero really hinges on two key strategies: 1) electrify everything, and 2) make clean electricity. Those two (strategies) alone will have the largest effect in reducing our emissions,” he says. “We need cars, stoves, heating systems—everything—to be electric, and then we need to build out wind, solar, and nuclear energy to supply those technologies with low or zero-carbon electricity.” Helveston suggests that making a play for net zero on a global scale is “really the only feasible path forward we have left at this point.”

ANU’s Longden says one of the consistent findings in modeling emissions reductions is that decarbonization will happen first in the electricity sector and then in transportation. “Decarbonizing the electricity sector usually happens first, followed by transport, especially when the uptake of electric vehicles is large,” he says. “In addition, improved energy efficiency and decreasing gas use for heating homes and buildings would achieve the bulk of these emissions reductions. So, the technologies we need to achieve notable emissions reductions already exist. The challenge is to help get them deployed across all groups, not just those who are first movers or are wealthy enough to absorb a larger upfront cost. Overcoming the upfront cost barrier is important, as many of these technologies save money over enough time.”

Strategy Analytics’ Sanchez points out that net-zero emissions on a global scale may be an elusive, maybe even impossible goal. “Normal human activity such as agriculture, manufacturing, air transport, and even natural activity such as volcanic eruptions (and) forest fires all have an impact on CO2 emissions,” he says. “There is also the issue of economic equity and developing nations not having the financial means to adopt ‘green’ technologies as quickly as more advanced economies. I think a more rational approach is continuous, incremental improvements in energy efficiency and reductions in CO2 emissions, as well as loan or grant programs to developing economies to transition to less carbon-intensive energy sources and economies.”

Net-zero emissions is a big ask, but the technologies exist to decarbonize electricity and a lot of transport. Longden says making sure solar, wind, and EV technologies are deployed across the globe in all types of communities is important and that is a challenge to tackle now. “Achieving net-zero emissions means that change has to occur across all sectors, households, cities, and towns,” he concludes. “It will not solely be achieved with rooftop solar and electric vehicles being deployed in wealthy suburbs in our main cities in wealthier countries. Changes need to be made across all countries, regions, cities, towns, and villages.”

For discussion’s sake, say this happens and all sectors, households, cities, and towns adopt change. Even in this scenario, is achieving the “bulk of emissions reductions” enough? Roger Aines, energy program chief scientist at the Lawrence Livermore Natl. Laboratory, believes there are really two issues that need to be addressed, and the second goes beyond just reaching for net-zero emissions. “There are two major problems here, and the first is we have to stop emitting. We have to replace fossil fuels with renewables, and we have to be more efficient,” he explains. “I’m focused on the longer-term problem of cleaning up the atmosphere of what’s already there.”

Aines is referring to removing CO2 from the atmosphere—the second of the two conundrums—and he says, thankfully, there are a lot of different ways to do it. “I’m optimistic because there are so many new ways to remove CO2 from the atmosphere,” he says. “When the XPRIZE announced the intermediate results for their $100 million carbon removal competition, they had (hundreds of) projects that qualified. That’s amazing. When you have that kind of intensity of development, good things are going to happen.” The XPRIZE competition, originally announced in February 2021, has since narrowed down the field of competitors to 15 milestone winners that are still competing through 2025 for an $80 million award.

While the innovators innovate by taking steps toward creating technologies that will remove carbon from the atmosphere, the path toward meeting climate goals and, ultimately, maybe even reaching net-zero emissions on a global scale, is one Forth Mobility’s Allen says is doable. How so? Because society already knows how to eliminate transportation carbon emissions, and now individuals, communities, governments, and regions need to take action and do it. “From landing on the moon to taking on COVID, again and again we’ve seen the huge impact of focusing our ingenuity on a shared goal,” Allen says. “Can we really reach zero emissions globally? Of course we can!”

Links for Further Learning:

- XPRIZE Milestone Winners for Carbon Removal

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

- IEA’s Global EV Outlook 2022 Executive Summary

Want to tweet about this article? Use hashtags #IoT #sustainability #AI #5G #cloud #edge #digitaltransformation #machinelearning #energy #electricity #renewables #fossilfuels #climatechange #netzero #zeroemissions #EVs #electricvehicles #transportation #solar #electrification #StrategyAnalytics #ForthMobility #XPRIZE #ParisAgreement