Green building. The green light has traditionally meant proceed, go, continue moving forward. As we move forward in our search for better living conditions, the building industry has adopted the term “green” as well. We are not referencing, except in rare occasion, buildings colored green. Yes. They may have greenery covered exterior walls—and in some case, interiors—but that is not where the “green” comes from.

The general focus on green buildings has been on energy conservation, emissions control, and efficiently using water and other resources. To paraphrase the words of Kermit the Frog from the Muppets, “It isn’t easy being green.” What paths are available? What makes a building green?

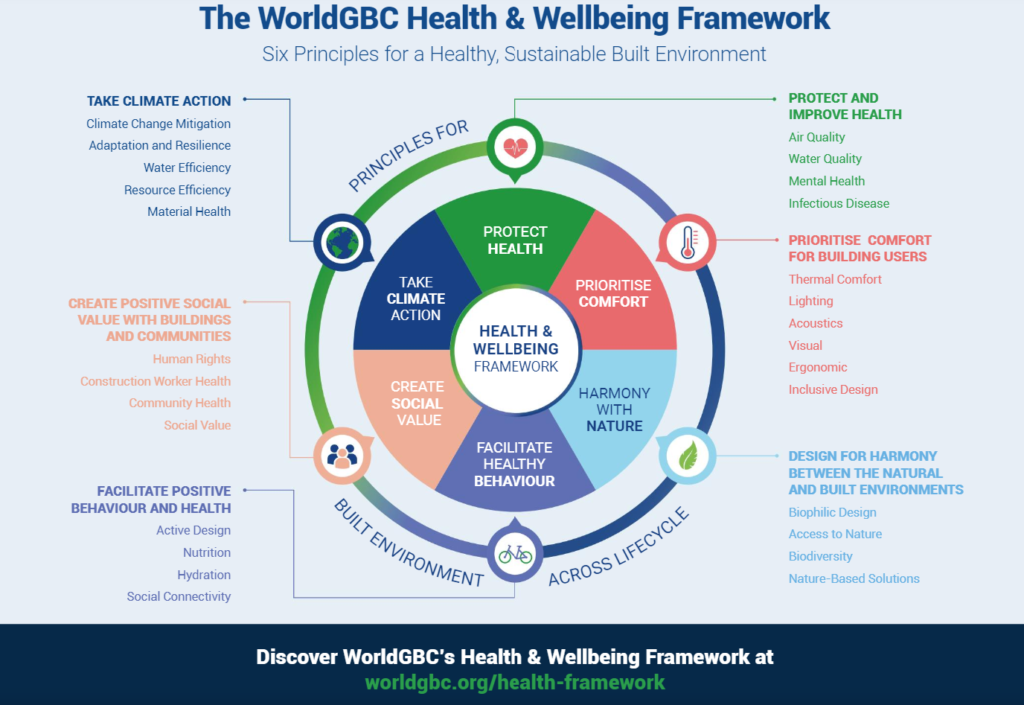

The WorldGBC (World Green Building Council) promotes just what you’d expect from its name—ways to create green buildings. According to the organization, a “green” building is a building that, in its design, construction, or operation, reduces or eliminates negative impacts, and can create positive impacts, on our climate and natural environment. Green buildings preserve precious natural resources and improve our quality of life.

Another voice, the U.S. EPA (Environmental Protection Agency), echoes that sentiment. The EPA says when referencing the construction phase, that “green building is the practice of creating structures and using processes that are environmentally responsible and resource-efficient throughout a building’s lifecycle from sitting to design, construction, operation, maintenance, renovation, and deconstruction.”

Green buildings are designed to reduce the overall impact of the built environment on human health and the natural environment by:

- Efficiently using energy, water, and other resources

- Protecting occupant health and improving employee productivity

- Reducing waste, pollution, and environmental degradation

It’s important to note the EPA adds health of the occupants to the list. The last few years have caused architects, engineers, and contractors to pay even more attention to that aspect of the green-building equation. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the concern for the public’s health and safety in buildings across the U.S. and across the globe. As states reopened communities, the AIA (American Institute of Architects) embarked on an initiative to explore how design strategies, backed by science, should be applied to a public health solution.

Reopening America: Strategies for Safer Buildings, is intended to provide design professionals, employers, building owners, and public officials with tools and resources for reducing risk when reoccupying buildings during the pandemic. As part of the initiative, AIA convened a team of architects, public health experts, engineers, and facility managers who conducted virtual design charrettes to develop strategies for:

- reducing the spread of pathogens in buildings

- accommodating physical distancing practices

- promoting mental well-being

- fulfilling alternative operational and functional expectations

The team developed strategies based on emerging science, infectious disease transmission data, epidemiological models, and research. These include:

- Strategies for assembly spaces, cafeterias, classrooms, entrances, gymnasiums, HVAC, locker rooms, and nurse’s offices.

- Strategies for checkout, HVAC, merchandising, and stock rooms.

- Strategies for dining facilities, amenity spaces, and individual units.

- Analysis and strategies for entrance, lobby, circulation, common amenities, service spaces, and individual dwelling units.

Employee expectations of post-pandemic indoor workspaces go beyond a “return to normal” and demonstrate a desire for spaces that put people in a better place, with an eye toward spaces that are more responsive to an ever-adapting world. This is according to a new survey “Making Space for a Resilient Future” by AWI (Armstrong World Industries) that revealed six trends that point to a need, and an opportunity, to approach the design of indoor workspaces more holistically, beyond merely fixing pandemic-related health and safety concerns.

Among these findings:

- 86% of respondents expect to feel very or somewhat safe in their workspace when they return to work.

- 83% of respondents expect to feel that their workspace will be prepared and adaptable for future events such as another pandemic or the changing climate.

- 84% of respondents expect to feel that their workspace will be an environment that is supportive of the well-being of people.

The survey comes as companies across the country, including Amazon, Duke Energy, Facebook, and Microsoft, have announced total or hybrid returns to work in the coming months and into the fall. Conducted among 1,000 U.S. workers who typically work in indoor environments, the survey in February 2021 explored employee feelings about and perceptions of work environments at offices, schools, and healthcare facilities as a result of what has been experienced due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The findings reflect the pandemic’s influence in heightening awareness and understanding of the importance and interconnectivity of healthy environments and one’s own personal environment. These themes are echoed in new 2030 commitments from AWI to cultivate thriving environments for employees and communities, more actively meet demands for healthier, circular products, and do more with less to preserve and protect the planet’s resources.

The six trends from the survey show that:

- Preparing indoor workspaces for returning workers isn’t just about COVID-related safety improvements.

- Employees are “giving permission” to landlords and employers to prepare workspace, not just for a “return to normal,” but for something that puts people in a better place, with an eye toward the future and being responsive to what is now being realized as an ever-adapting world.

- Addressing indoor workspace should move beyond just fixing pandemic-related concerns toward approaches that are more holistic in nature and embrace resilience and well-being.

- Employers must view indoor workspaces as an asset for attracting and retaining talent and replicating the themes of comfort and well-being employees have experienced as they have worked from home.

- Volatility and ongoing changes to spaces caused by pandemics, climate change, and more are here to stay, but working safely and comfortably within indoor environments is possible. Workspaces can and should be created to serve as environments in which people feel altogether better.

- What makes a workspace safer can also make it healthier, more sustainable, and better for total well-being.

And the interior isn’t the only aspect of the building that can be improved, made greener. Take academic buildings and how they interact with their environment. Looking at a 200-year-old Amherst College’s science center represents meticulous craft, layered transparency, and academic connectivity. Situated against the Pelham Hills, the center consists of five buildings within a campus greenway with a central daylight-filled commons that serves as a social heart. Warmly welcoming the entire academic community, the center offers an ultra-transparent window into science.

The center, a campus-scaled approach, is composed of two high-energy laboratory wings tucked into the hillside to the east and three low-intensity pavilions that crawl up the hill toward the college’s academic core. Through its overall organization and detailing, the design promotes transparency and interaction. The laboratories and pavilions all open onto the commons, fostering community and advancing the college’s goal to encourage interaction among students and the sciences.

A distinctive roof covering the commons is the building’s unifying feature. A series of finely crafted skylights run the length of the building, animating the roof’s form, and boosting the quality of daylight that streams into the space below. In addition to providing both natural and artificial light, the roof also serves several other functions at once: its photovoltaic panels generate electricity, its shape and materials support acoustic control, and it offers radiant heat and cooling for the commons.

A palette of clearly articulated and minimally expressed natural materials permeate the project, setting the contemporary center into the traditional legacy that surrounds it. From handmade gray bricks that evoke local stone walls to custom weathering steel screens that echo the tones of nearby structures, the team embraced craft and detailing to help tie the center to its context.

Indeed, as people have more access to green environments, in urban areas and on campus, the benefits can improve health and disposition. The U.S. CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) reports that people who have more access to green environments, such as parks and trails, tend to walk and be more physically active than those with limited access. The closer people live to a park and the safer they feel in the park, the more likely they are to walk or bike to those places and use the park for physical activity.

Parks and trails that are well-designed offer many benefits. They provide a place where people can be physically active to reduce stress, which can improve their mental health. They also provide a place where neighbors can meet, which improves community connections.

Parks can provide environmental benefits as well, by reducing air and water pollution, protecting areas from inappropriate development, and mitigating urban heat islands. They help people reduce their risk of illness and injury by providing safe spaces where people can play and exercise away from busy streets and commercial zones.

But the CDC says less than half of people in the United States live within half a mile of a park. Even fewer people live in a community that has both safe streets for walking and access to places for physical activity like parks.

What can architects, builders, and owners do to provide those benefits? Design communities that support safe and easy places for people to walk, bike, wheelchair roll, and do other physical activities. How?

- Work with a local coalition to locate and improve parks, trails, and recreational facilities near homes, schools, worksites, and other places where people regularly spend time. Consider using mapping tools to assess the location and quality of current parks (see Resources below).

- Work with communities to get their input on how to create or improve local recreation areas and green spaces. Use welcoming designs that represent all community members. Consider design elements like walking loops to promote activity, benches where people can take breaks, or shade for cooling and sun shelter.

- Increase access points to recreation areas and green spaces or locate them along public rights of way so they are more accessible to community members.

- Work closely with local planning and transportation departments to build and maintain sidewalks, crosswalks, bike racks, bike paths, and shade trees, as well as routes within and between parks, trails, and other key destinations.

- Work with local planning and transportation departments to update city policies to include goals designed to increase access to park, trails, and recreational facilities. For example, a city might require that new developments include green space.

- Work with community partners and municipal departments to set up shared-use agreements to increase public access to places to be physically active. These places may include school yards, municipal building grounds, or university pools and training facilities.

- Consider closing parks to motor vehicles and opening streets to pedestrians in and around parks.

- Offer inclusive programs that are based on the needs of the community and address barriers, including physical limitations, safety concerns, cultural preferences, and costs.

- Promote equitable open streets and play streets to provide people with more spaces to be active.

- Partner with local organizations to bring inclusive community programs to existing parks, trails, and green spaces.

- Prioritize resources toward areas and populations that lack access to parks or other safe places to be physically active.

- Provide wayfinding signs to help people find safe places to be active. These signs should include information about accessibility for people with mobility or other limitations.

- Use low-cost removable materials and equipment to create pop-up parks and show how traffic can be slowed (called traffic calming) along routes to parks. Get feedback from the community on ways to make permanent changes to improve park access and facilities.

In June 2020, the U.S. GBC (U.S. Green Building Council) unveiled four new pilot credits for buildings that are meant to address sustainability needs for project teams in the time of COVID-19. The credits outline some best practices for sustainability—in the areas of disinfection, workplace reoccupancy, indoor air quality, and water quality—that also align with public health guidelines. These credits can be used by LEED projects that are certified or are undergoing certification.

1. Safety First: Cleaning and Disinfecting Your Space. This credit requires buildings to follow LEED’s green cleaning best practices, and it also meets the guidelines of the CDC relative to COVID-19.

2. Safety First: Re-Entering Your Workspace. For this credit, LEED consulted the AIA and its Reoccupancy Assessment Tool, which requires transparent reporting and evaluating decisions to encourage continuous improvement. The credit also requires that buildings have a re-entry plan that includes things like access control, social distancing, touch point reduction, and communication.

3. Safety First: Building Water System Recommissioning. For buildings that have been closed for weeks or months, low or non-existent occupancy can cause issues within the building’s water system, including stagnant water that is unsafe to drink or use. With guidelines from the CDC and EPA, this credit requires buildings to develop and implement a water management plan, coordinate with local water and public health authorities, and communicate water system activities and associated risks to occupants—as well as take steps to address water quality.

4. Safety First: Managing Indoor Air Quality During COVID-19. This credit builds on LEED’s existing indoor air quality requirements and credits and requires buildings to determine temporary adjustments to their ventilation approach that might minimize the spread of COVID-19 through the air. It also incorporates guidelines from the CDC.

As we’ve seen, the COVID-19 pandemic has reordered much of the daily life for people at all stages of life, school children to seniors and especially those at the later stages of life and living in nursing homes and care facilities. All people can benefit from the greening of existing and future buildings. It’s no longer just energy we need to be concerned about, it’s every aspect of every building, new and old. That’s how we get greener spaces.

Want to tweet about this article? Use hashtags #construction #IoT #sustainability #AI #5G #cloud #edge #futureofwork #infrastructure